Having knowledge of weed and insect activity in future corn fields is an important step to help maximize corn yield potential. This is especially important in no-till and continuous corn.

Weed Scouting

Scouting future corn fields in the fall and early spring can help determine which weeds are present, their population, their growth stage, and best management practices for control.1 Good weed control during the first four to six weeks after planting is critical for maintaining yield potential. A clean start helps conserve moisture and nutrients for the crop, establish good seed-to-soil contact, ensure seedlings are not shaded or competing for resources, and prevent weeds from binding up planters. Winter annual weeds that emerge in late summer through fall can overwinter and set seed in the spring and early summer. Small weed patches may not seem economical to control; however, these patches may have time to produce seed and add to the soil weed-seed bank before a burndown application or tillage is accomplished.2 Recognizing annual weeds such as waterhemp (Amaranthus tuberculaatus) and Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) in the fall is important as they emerge later in the spring and require diligent management with residual herbicides.

Perennial weeds in no-till systems can be difficult to control because their root structures remain intact instead of being broken up as in tilled systems. Additionally, in no-till systems, weeds that produce prolific amounts of seed that germinate at or near the soil surface such as marestail (Conyza canadensis), waterhemp, foxtails (Setaria species), and others can become widespread, and many of these species have developed resistance to glyphosate and other herbicide modes of action.3 It is important to control these weeds when they are less than four-inches tall, which can require control as soon as equipment can enter the field.2 Starting clean and staying clean is important for weeds like marestail, waterhemp and Palmer amaranth, especially in soybean fields.

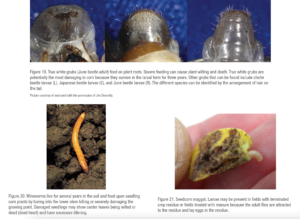

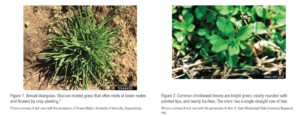

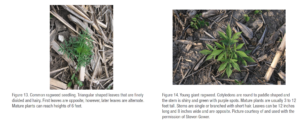

Common Winter Annual and Perennial Weeds (Figures 1 through 18)

Common weeds to scout for in the fall include annual bluegrass (Poa annua), common chickweed (Stellaria media), dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), downy brome (Bromus tectorum), cressleaf groundsel (butterweed) (Senecio glabellus), field pennycress (Thlaspi arvense), henbit (Lamium amplexicaule), marestail (horseweed), mouseear chickweed (Cerastium vulgatum), purple deadnettle (Lamium purpureum), Shepherd’s purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris), wild carrot (Daucus carota), wild mustard (Brassica kaber), and yellow rocket (Barbarea vulgaris). Weeds that usually emerge early spring are common lambsquarters (Chenopodium album), Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense), and common (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) and giant ragweed (Ambrosia trifida).4,5,6

Insect Activity and Scouting

The potential for an insect to become a pest in future corn fields depends on its life cycle, feeding habit, and tillage practices. Some insects, such as wireworms and true white grubs overwinter as larva, while others such as corn borers, overwinter in their pupal growth stage. Those overwintering as larvae can be potentially damaging to newly planted seeds and emerging seedlings while pupating insects can cause damage later in the growing season. Certain agronomic practices, such as no-till, continuous corn, manure applications, and cover crop growth can provide a medium for insects to thrive and become a concern. Life cycle knowledge is important as some insects, such as black cutworm and corn earworm, do not overwinter in the Midwest; therefore, potential infestations are dependent on southerly winds bringing the moths from overwintering southern locations to the Midwest.

Scouting includes digging around seedlings to look for wireworm, true white grub, or seedcorn maggot damage, inspecting corn leaf tissue around three feet tall for corn borer eggs, digging corn roots to evaluate for corn rootworm feeding, and placing sticky traps in soybean fields to monitor for western corn rootworm variant beetles. Scouting should be random and replicated through a field to get a representative sampling of insect activity as the feeding may be isolated to one area or widespread. Equipment for insect scouting may include a digging tool (garden trowel or spade), tape measure, a small vial or container filled with isopropyl alcohol to collect insect samples, and a bucket for root samples.

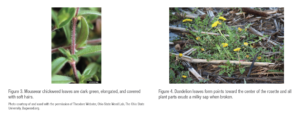

Damage from true white grubs (June beetle adult) in soybean or corn fields can be an indication that damage may occur in the next corn crop because the larvae can be present for three years (Figure 19).10 Other grubs including those of chafer beetle and Japanese beetle may be present. Identification between the species can be determined by observing the formation of tail hair, also known as the raster pattern (Figure 19).

Wireworms (Figure 20) can damage corn by boring into the growing point and killing or severely damaging it which can be observed as wilted or dead whorls. Buried grain-based bait stations can be used in the spring to help identify the potential for wireworm damage to seedling corn.11 If wireworms are found in the bait, consideration should be given to applying an insecticide at planting.

Residue from terminated cover and forage crops and fields treated with manure can be attractive to the adult fly of seedcorn maggot. The maggots hatch from eggs laid in the mat and feed on corn seed (Figure 21). Corn planted in these fields has the potential for seedcorn maggot damage.12

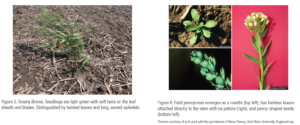

In areas where western corn rootworm (WCR) variant beetles are present, soybean fields should be scouted for their presence and population using sticky traps (Figure 22).13,14 Prior to the WCR adapting, WCR beetles fed and laid eggs in corn; however, the variant can survive by feeding on soybean plants and lays eggs in the soil surrounding the plants. The eggs laid in the soybean field soil can result in rootworm larvae feeding on future corn roots. The threshold in soybean fields is 1.5 western corn rootworm beetles/trap/day.15

Additionally, soybean fields with a high population of volunteer corn may have supported rootworm larvae and adults. Though not a usual problem, Japanese beetles can also be found feeding on soybean plants and can be an indication that they could infest a future corn field (Figures 19 and 22).

In continuous corn fields, the presence of European or southwestern corn borers in the current corn crop should be noted (Figure 23).16,17 The moths resulting from the overwintering larvae can lay eggs on corn leaves that result in the larvae feeding on leaves and stalks. If borers are present in previous continuous corn, consider using corn products protected with Bacillus thuringiensis (B.t.) traits. The moths will travel to the most attractive corn plants to lay eggs; therefore, non-continuous corn may be at risk of an infestation. Scouting during the growing season should be conducted in non-continuous corn.